The Trans-Pacific Partnership and the need for KORUS

June 27, 2011

Bound to fail

July 25, 2011By Prashanth Parameswaran |

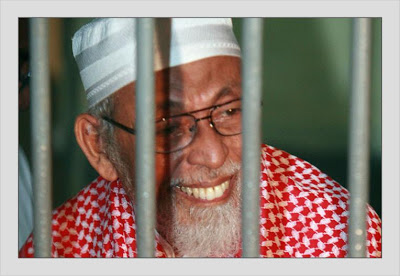

Last month, Indonesian cleric Abu Bakar Bashir was found guilty of terrorism charges and jailed for 15 years. The 72-year old Muslim cleric, which some consider the spiritual leader of Jemaah Islamiyah, the Southeast Asian offshoot of al-Qaeda, is widely believed to have inspired the deadly Bali bombings of 2002.

Though this is his third arrest and imprisonment on terrorism-related charges, the other two were much shorter stints while this is seen as a life sentence. The conviction this time was for organizing and financing a terrorist training camp called Al-Qaeda in Aceh, where dozens of militants were allegedly plotting to assassinate Indonesia’s president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

While Indonesian authorities deserve credit for effectively putting the country’s most notorious Islamist behind bars for the rest of his life, it remains unclear to what extent this actually stems his potential ideological influence on others both from within prison and beyond.

In most cases, imprisonment tends to at least somewhat diminish the threat the prisoner could otherwise pose to society. In Indonesia, however, experts have long warned that prisons are not only poor barriers against, but good incubators of terrorism.

Last year, a report by Carl Ungerer from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, based on in-depth interviews with 33 terrorists in Indonesian prisons, concluded that some prisoners were actually contributing to a surge in violent jihadi literature while in captivity, and that a full 30 percent shared Al-Qaeda’s view of global jihad against the West and were immune to de-radicalization.

And as early as 2007, the International Crisis Group had warned that while Jakarta had achieved some success with regard to its de-radicalization programs and was beginning to address prison reform, more needed to be done, including establishing an on-the-job training program for prison administrators, addressing corruption, and increasing coordination between correction officials.

Furthermore, while Bashir the man has been in captivity since last August, the jihadist ideology he helped spawn has remained free to wreak havoc on Indonesian society, and will probably continue to do so in the near future.

The appetite for high-profile, high-casualty attacks on ‘Western targets’ such as the Bali bombings of 2002 and 2005, the Australian Embassy in 2004, or the J.W. Marriot Hotel bombings in 2003 and the Ritz-Carlton hotel in 2009 may have dried up. But other more localized, smaller-scale manifestations of religious violence targeting institutions like the police and other minorities, whether by splinter factions or ‘lone wolves,’ remain a major concern as militants try to undermine pluralism and push for an Islamic state.

Since Bashir was taken into custody last August, mobs have continued to take the law into their own hands, slaying members of the Muslim Ahmadiyya sect which was banned in 2008, razing churches and beating Christians to death over a blasphemy case earlier this year, and staging sporadic violent protests against unregistered Christian churches, karaoke bars and other ‘places of immorality’ organized by local clerics. Such religious violence can often be a prelude to more radical acts thereafter, such as the case of Muhammad Syarif, a member of Bashir’s Jema’ah Ansharut Tauhid who blew himself up at a police station mosque last month, killing one and injuring 28 people.

All this suggests that while the most prominent face of terror in Indonesia is now behind bars, the country faces an uphill struggle against the many faces of extremism still prevalent on its streets.

Prashanth Parameswaran was a research assistant at the Project 2049 Institute and is a Master of Arts candidate at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University.