China’s Air Defense Identification System: The Role of PLA Air Surveillance

May 9, 2014

China’s Relations with Taiwan and North Korea

June 5, 2014By Samuel Mun |

Over the past two decades, the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) have developed a “strategic cooperative partnership†reflected through a sharp increase in bilateral trade, security dialogues, and more recently, frequent discussions on China’s potential role in addressing North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. However, while the ROK-PRC partnership is at a historic high point, this relationship faces significant obstacles. These limitations in their ties reinforce the paramount importance of the U.S.-ROK alliance in face of a belligerent North Korea and rising China.

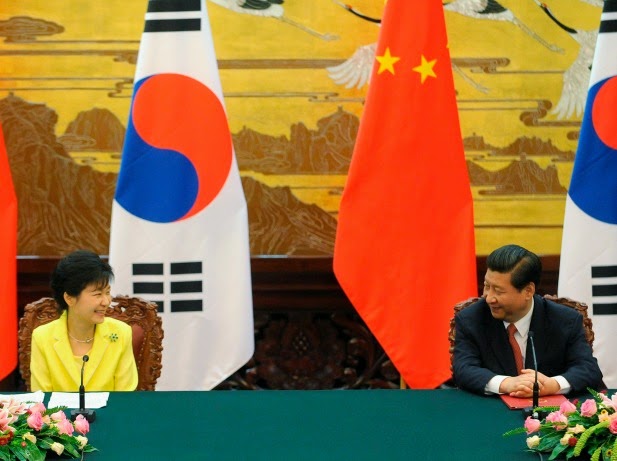

South Korean President Park Geun-hye’s state visit to China in 2013 demonstrated the immense progress made in ROK-PRC relations since the two countries normalized ties in 1992. Today, South Korea’s trade volume with China has grown to exceed its bilateral trade with the United States and Japan combined, and negotiations for a South Korea-China free trade agreement by 2015 were prioritized during the summit between President Park and President Xi. The two leaders also agreed to establish a high-level security dialogue between Seoul and Beijing and issued a joint-statement calling for the denuclearization of North Korea.

South Korea’s interest in building its partnership with China also goes beyond economic ties and China’s apparent leverage in reining in North Korea. Another source of overlap and agreement between Seoul and Beijing is their shared discord with Japan, against whom they share historical animosities related to Japan’s colonial and wartime legacies in the first half of the 20th century. For example, China’s opening of an exhibition (a request made by Park during her 2013 state visit to China) commemorating Ahn Jung-geun, a Korean who assassinated the first Japanese overseer of colonial Korea, showed further ROK-PRC alignment despite U.S. efforts to promote cooperation between Japan and South Korea.

Although political and economic ties between Seoul and Beijing are warm, decision-makers in Seoul must remain cognizant of Beijing’s strategic goals in the region that are inherently antithetical to South Korea’s security interests. In other words, Chinese efforts to alter the regional status quo and undermine the U.S.-led security architecture in Northeast Asia hinder South Korea’s ability to defend itself from North Korea, which remains an existential threat to South Korea.

China’s efforts to stifle South Korea’s cooperation with the United States—South Korea’s sole security guarantor for over 60 years—highlights the limits of the South Korea-China relationship. For example, in response to annual U.S.-ROK joint military drills intended to increase deterrence against North Korea and improve interoperability, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying asserted that “China is opposed to any move that may result in tensions in the region, whether they be joint drills or the threat of conducting nuclear tests.†Furthermore, at a conference this month in Shanghai, Xi Jinping warned against the strengthening of alliances in the region. And while Xi did not mention the United States, it was clear that he was in part referring to U.S. efforts to improve trilateral cooperation with Japan and South Korea.

It is this very mechanism, however, that directly lends to greater deterrence and preparedness against North Korean provocations and bellicosity. U.S.-Japan-ROK trilateral coordination in anti-submarine warfare, mine warfare, and ballistic missile defense will be critical in a military contingency on the Korean peninsula. South Korea and China may empathize with each other’s experience under Japanese colonial rule, but South Korea’s security environment demands that it coordinate more closely with the United States and Japan on security issues. Such coordination is salient particularly for scenarios where the United States will launch operations on and around the Korean peninsula from its bases in Japan.

To what extent will South Korea continue to build ties with China? Public opinion polls by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies from March 2014 indicate that “70.4% of South Koreans [state] that Korea should strengthen the alliance with the United States to check China,†and “53.4% agreed that Korea should strengthen the alliance with the United States even at the risk of making China uncomfortable.†The polling data also suggests that warm South Korea-China ties may not necessarily translate into substantial security cooperation, as China’s reluctance to condemn North Korea’s sinking of the South Korean corvette, Cheonan, and shelling of Yeonpyeong Island in 2010 are not too distant memories for South Koreans who sought China’s support in censuring North Korea.

As the United States rebalances to the Asia-Pacific in response to China’s rise, South Korea’s proverbial status as a “shrimp among whales†is increasingly relevant. Despite Seoul’s recent political and economic leanings toward Beijing, divergent regional security interests reveal clear limits in how far South Korea can balance toward China. Conversely, the U.S.-ROK alliance since 1953 has deterred war on the Korean peninsula and evolved into a “global partnership†rooted in shared values and strategic interests. As such, the U.S.-ROK alliance will remain the indispensable element to South Korea’s security and prosperity for the foreseeable future.